The Attraction and Trouble With Continuation Vehicles for LPs - Part 2

As discussed in the last post, Continuation Vehicles (CVs) are booming and offer good risk-adjusted return outperforming buyouts across all quartiles.

But there is more to it than that. So this post takes a closer look at the trouble with continuation vehicles from the LP’s perspective. But first a quick summary:

- Tight Timelines: LPs often face compressed decision-making periods, challenging internal governance structures

- Resource Constraints: Assessing CV opportunities demands significant expertise and resources, which some LPs may lack

- Valuation Concerns: Determining fair market value is complex, especially when GPs manage both sides of the transaction

- Shifted Responsibilities: CVs transfer exit decisions to LPs, deviating from the traditional GP-led exit strategy

- No should be the default answer: if proceeding have a well designed framework that allows for a quick decline

—

Challenges Faced by LPs

1. Tight Timelines

Continuation vehicles often come with compressed timelines, sometimes as little as 2 – 4 weeks for LPs to assess, approve, and respond. These are complex transactions, often involving hundreds of pages of documentation, revised economic terms, and strategic considerations.

Yet LPs are expected to react as though this is a routine consent process!

For many institutional investors, especially those with layered internal approval processes, this timeline is simply unworkable.

Investment committees might not meet frequently enough, and risk teams may not have the capacity to diligence a nuanced secondary structure in such short order. The result is a default to either rolling over on trust or selling at a discount, neither of which serves the LP’s interests well.

2. Internal Governance Constraints

Even for sophisticated LPs, governance structures were often not designed to accommodate the unique demands of continuation vehicles.

Traditionally, LPs commit capital up front and then rely on GPs to make key decisions, including exits. CVs reverse that script, requiring LPs to take an active position mid-lifecycle.

Many investors simply don’t have pre-defined policies or delegated authority to deal with these decisions. Do they treat a CV like a re-up? A new investment? A secondary sale?

Internal ambiguity leads to delays, bottlenecks, and inconsistent outcomes—especially across large institutional platforms where multiple stakeholders are involved.

3. Resource and Expertise Constraints

Properly evaluating a continuation vehicle requires significant time, domain knowledge, and legal/financial sophistication. LPs will often need to assess

- The asset’s intrinsic value

- The rationale for continued ownership

- Revised fee and carry structures

- Governance rights in the new vehicle

- The GP’s motivations and alignment

Yet the teams within LP organizations responsible for secondary decisions are often lean, and may not have access to the same level of information or analysis that GPs use internally to justify these transactions. In the worst case it is left to the primary team, who additionally may not have the expertise to deal with CVs.

This asymmetry of information can tilt the playing field and leave LPs making multi-year reinvestment decisions based on limited transparency.

4. Valuation and Pricing Uncertainty

One of the most contentious elements of continuation vehicles is pricing. These are often “negotiated” transactions, yet often the GP sits on both sides of the table, acting as seller from the old fund and buyer on behalf of the new vehicle. This naturally raises conflict-of-interest concerns.

While third-party fairness opinions are commonly included, they are usually GP-selected and may not reflect full market dynamics. There’s no broad auction process, and LPs must take it on faith that the price reflects fair value.

The irony is that if these are “trophy assets,” why aren’t more buyers in the market, bidding up the price? If they are so obviously compelling, shouldn’t competitive tension be driving valuations higher, rather than LPs being offered a take-it-or-leave-it discount?

5. Misalignment of Incentives and Fees

CVs can quietly reset economics for the GP, allowing them to establish a new carry structure and sometimes a full fee schedule, often with minimal incremental effort. After all, there’s no origination, no auction, and (in theory) less value creation left to realize.

LPs should be asking themselves: Should this really cost the same as a traditional fund investment?

If the GP is transferring a stable, high-performing company from one fund / vehicle to another, without a sale process, board replacement, or turnaround strategy, then full freight fees and carry may not be warranted.

This is especially true when the GP stands to earn carry twice – once from the old fund (if a “step-up” occurs), and again from the CV. The potential for double-dipping is real, and LPs must scrutinize how aligned the GP remains with both the old and new investor base.

6. The Role Reversal in Decision-Making

This might be the biggest challenge: CVs push the decision to divest or stay invested back onto the LP. This turns the GP/LP model on its head.

LPs invest in private equity precisely because GPs are expected to manage the timing of acquisitions and exits. That’s part of the value proposition. But with CVs, the GP defers this responsibility to the LP: “Do you want to stay in, or get out?”

For an LP, that’s a decision made with less access to management, less visibility into the growth plan, and less control over governance than the GP. And yet, the LP is now on the hook for making a judgment call on asset retention vs. liquidity, despite being less informed and less empowered.

This isn’t what LPs signed up for. And while some may relish the flexibility, many feel it violates the spirit of the relationship: GPs manage; LPs back them to do so. And many LPs may feel ill-equipped to make such determinations.

Recommendations for Limited Partners

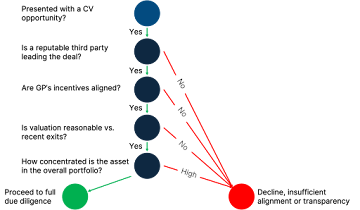

Though compelling, given the complexities surrounding CVs, LPs should approach such opportunities with caution, and in most cases the default answer should probably be a fast no.

If deciding to proceed a more structured evaluation framework can aid in decision-making and facilitate moving at speed

- Assess Third-Party Involvement: Is a reputable third party leading the transaction, ensuring impartiality and market validation?

- Evaluate GP Commitment: How much capital is the GP rolling into the CV? A significant commitment can indicate confidence in the asset’s future performance.

- Analyze Valuation Uplift: Compare the asset’s valuation markup to the GP’s recent exits. Is the markup justified based on performance and market conditions?

- Consider Portfolio Impact: What percentage of the fund’s NAV and Cost is being allocated to CVs? Excessive allocation may signal overreliance on such structures.

Below this has been turned into a schematic fast and easy to use decision matrix.

Figure 1: LP Decision Matrix for Evaluating CVs

In summary

Continuation vehicles offer a mechanism for GPs to retain high-quality assets and provide compelling risk-return adjusted liquidity options to LPs. However, they also introduce challenges related to decision-making timelines, resource requirements, valuation complexities, and shifts in traditional roles.

LPs must conduct thorough due diligence and critically assess each opportunity to ensure alignment with their investment objectives and fiduciary responsibilities.

Stay Illiquid

Kasper

More Insights

Balentic Edge

Sign up to keep up to date with the latest news and updates.

© 2025 Balentic ApS. CVR: 44034255. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy | Terms of Service

The Balentic website and Orca are, and are expected to continue to be, under development. Consequently, some of the features described in this Overview and/or on the website may not yet be available or may work differently. Some features may furthermore not be available to all users.