The Venture Deficit: Can Europe Catch Up?

Despite talent and innovation, fragmented markets and cautious capital leave Europe behind in scaling tech. What will it take to change course?

I’m writing this piece in connection with joining a panel at the Nordic Fintech Week on “Unlocking private capital for Europe’s tech future”. I was invited because I have seen this challenge from both sides: as an allocator to venture funds and now as a founder raising – or at least attempting to raise – capital from VCs.

I’m not a policy expert, but an experienced and, I like to think informed, practitioner. My view is part optimistic, part sceptical: Europe has talent and ideas, yet struggles to scale them and many end up raising capital in the US. Furthermore, in my view, the issue isn’t just capital – it’s conviction. Europe doesn’t lack money; it lacks belief in growth.

“Europe has the savings; the United States has the venture capital”

Jean-Claude Trichet (ex-ECB President)

Executive Summary

- Europe has talent and ideas but lacks the capital depth and conviction to build global tech champions

- Reliance on soft money and sub-scale VC funds fosters complacency rather than a true risk-taking culture

- Risk aversion, regulatory fragmentation, and under-allocation by pensions and insurers hold back growth equity and venture capital

- The Draghi Report outlined solutions, single market, Solvency II reform, deeper capital markets, but implementation is slow

- Fintech is the stress test: if Europe can fix scaling here, the template extends to AI, climate tech, and deep tech

The Long Road to Funding for European Founders

Europe’s Tech Moment - and Its Capital Gap

Europe sits at a crossroads. On the one hand, the continent is rich with innovation in fintech, AI, deep tech, and sustainability. On the other, it struggles to scale these breakthroughs into global champions. The missing link is not just more money, but the right kind of money: risk-tolerant, long-term private capital that fuels ambition.

Why It Matters

Private capital is more than a funding source. It is a signal of conviction, a mechanism for scaling, and a filter that disciplines ambition. Europe already produces 26% of global venture funding but captures only around 15% of exit value, a telling mismatch. Further, since 2015, nearly 90% of all $10bn+ venture-backed exits have taken place in the US, with Europe contributing barely a handful.

The result is that great companies born in Europe too often scale elsewhere.

Europe’s Structural Headwinds

A Culture of Safety

Howard Marks once said risk is not only the probability of loss, it is also the risk of missing opportunities and the risk of not taking enough risk. Europe leans too heavily on the first definition and excels in risk aversion – both of which are an obstacle to generating outsized returns in venture. In the meantime, many founders face cautious investors, smaller cheques, and valuations that cap ambition.

Fragmentation and Friction

The EU’s regulatory environment is a maze. A fintech founder in Europe may need one law firm per country; their US counterpart hires one and immediately accesses a 300 million–person market. The Draghi Report called for a true single capital market, but implementation is painfully slow – a year on, not much of anything has happened.

Institutional Under-Allocation

Pension funds and insurers, Europe’s natural pools of patient capital, remain under-allocated to venture and growth. Under Solvency II, insurers are penalised for holding long-term equity. By contrast, Canadian peers such as Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan and CPP Investments allocate 7–10% or more to venture and growth platforms.

The Soft Money Dilemma

A distinctive feature of European venture is its reliance on subsidies, grants, and soft funding from public institutions such as the EIF or national development banks. These programmes have played a role in seeding the ecosystem, but they also raise a harder question: do they foster a genuine risk-taking culture, or do they inadvertently breed complacency?

For institutional LPs, heavy dependence on public anchors can be a warning sign. Soft money can mask weak investment theses, delay hard choices about scale, and create fund managers who optimise for access to soft money and living off fees rather than for finding fund-returning companies. It also risks signalling to private investors that venture in Europe cannot stand on its own.

The point is not to discard public capital altogether, every ecosystem has needed it at some stage, but to recognise its limits. True conviction comes when private institutions allocate with scale and discipline. That is the shift Europe must make if it wants to generate global winners rather than perpetually nurturing promising but sub-scale players.

The Problem of Sub-Scale Funds

European venture often prides itself on breadth, but in practice that means capital is spread far and wide across hundreds of small funds. As Bilbo Baggins put it in The Lord of the Rings, it feels “like butter scraped over too much bread” – too thin to matter.

The result is a structural dilemma. Sub-scale funds cannot both build concentrated, conviction-driven portfolios and still hold meaningful stakes through multiple rounds. They are forced into impossible positions: spread thin across too many names, unable to double down on winners, and left watching as better-capitalised global funds take over the scaling phase.

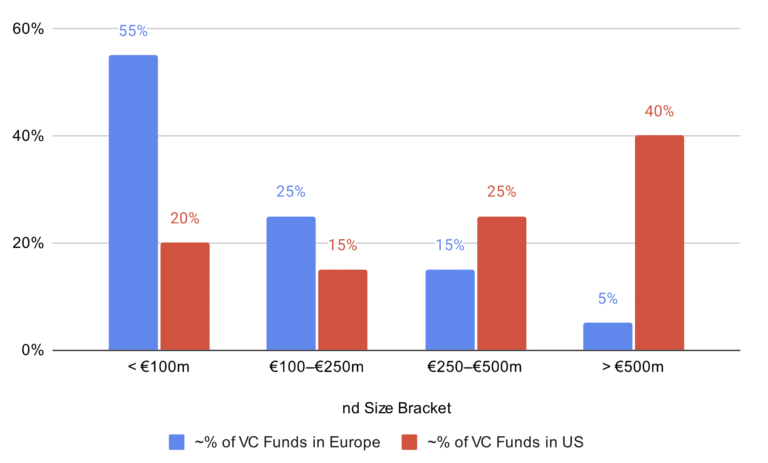

It is telling that in Europe, a Fund III raising more than €500 million is almost as rare as seeing an actual real life unicorn on the street. In the US, by contrast, a half-billion fund is barely mid-market. Size alone does not guarantee success, but without sufficient firepower, even the best European managers struggle to back founders at scale.

Figure 1: In Europe, the median VC fund is well below €150m; in the US, mid-market funds often exceed €500m.

Source: Pitchbook, Balentic Analysis 2025

As illustrated in Figure 1, European VC funds remain structurally sub-scale. More than half are under €100 million, leaving managers with little capacity to lead rounds, support follow-ons, or hold meaningful stakes. In the US, by contrast, nearly half of all funds exceed €500 million – the scale needed to back winners through multiple funding cycles.

For LPs, this size disparity matters: small funds may be nimble, but they rarely generate the fund-returning outliers that justify institutional venture allocations.

The Complacency Trap

Europe’s venture capital industry has grown in visibility, but scale has not yet brought the sharpness that global competition demands. Too many funds are seemingly content to remain small, anchored by soft money, and benchmark themselves against median IRRs rather than outlier performance. In a power-law asset class, that is complacency, not strategy.

For LPs, this is frustrating. They hear plenty of talk about unicorn counts and ecosystem vibrancy, but too few examples of fund-returners or conviction bets. Additionally, the challenge is not just returns but governance drag: committing €20m to a €100m fund can take as much time and legal effort as a €200m ticket to a global platform. The bandwidth rarely feels justified

For founders, it can be worse: capital that comes with strings, slow decision-making, or valuations designed to limit downside rather than amplify upside.

Without pressure to professionalise, to raise real pools of capital, to take risk on conviction, to build the next generation of fund-returners, Europe risks producing a venture ecosystem that is busy, well-meaning, but ultimately second-tier.

This creates a double bind for LPs

Smaller funds may generate attractive early multiples but rarely produce the fund-returning outliers that make venture allocations worthwhile. Portfolio construction is stretched, governance costs are high relative to commitments, and performance dispersion is extreme.

In short, sub-scale funds are often unattractive for institutional investors – too small to move the needle, too fragile to weather cycles, and too reliant on soft anchors. If Europe wants to crowd in pensions and insurers at scale, it must create venture firms with the capital base and conviction to back winners all the way.

The US Contrast

The US mindset is scale-first. Investors back founders with larger cheques, faster timelines, and valuations that reward ambition. Cultural framing matters: American founders hear “we’re lucky to be on your journey”; Europeans often hear “congratulations, we funded you.”

The difference shows up in outcomes: US venture consistently produces $10bn+ decacorns, while Europe still obsesses over unicorn counts coined a decade ago.

The Solutions Are Not Out Of Reach

For policymakers, the priority should be creating true mutual recognition and passporting across the EU. One authorisation ought to be valid everywhere, not duplicated across 27 jurisdictions. Alongside this, Solvency II rules need to be reformed so that long-term equity is treated as a strategic asset, not an exotic one. Finally, Europe would benefit from genuine tax symmetry – allowing the deductibility of losses on risk capital, as the UK’s EIS has already shown can work in practice.

Practitioners, both LPs and GPs, also have an important role to play.

For LPs, the shift must be from cautious “toe-dipping” towards programmatic venture and growth allocations, using Canadian pension models and maybe even US endowments as a benchmark.

For GPs, professionalisation is the watchword: less reliance on soft money, more emphasis on building scale, and greater diversity of operator DNA in investment teams. Above all, the focus must be on backing fund-returners, not chasing unicorns, and on scaling funds with private institutional capital.

Founders, we too, must think differently. Building with conviction means designing for global scale early, recognising that Europe’s fragmentation often makes a US or Asian expansion inevitable. At the same time, regulation should not be seen as a drag but as part of the strategy. Those who master compliance and licensing quickly often discover it becomes a competitive moat.

Why Fintech Is the Stress Test

Fintech is among Europe’s most regulated and capital-intensive sectors. Licensing, compliance, and balance-sheet needs make it a crucible for scaling. If Europe can enable fintech founders to scale with one-file passporting and capital-friendly treatment, it creates a template for AI, climate tech, and deep tech.

Values Still Matter

Europe should not blindly copy Silicon Valley. Its strengths, trust, consumer protection, and long-term orientation, are worth keeping. But values without velocity and a belief in growth and risk taking mean stagnation.

The goal is clarity plus conviction: an ecosystem that funds tomorrow while holding on to Europe’s values-driven edge.

From Startup Continent to Scale-Up Superpower

Europe is not short of ambition, only conviction. The choice is whether to remain a continent of startups or to become a scale-up superpower. That requires a mindset shift: capital follows clarity, risk is strategic, and fintech is our proving ground.

Stay Illiquid!

Kasper

—

More Insights

Balentic Edge

Sign up to keep up to date with the latest news and updates.

© 2025 Balentic ApS. CVR: 44034255. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy | Terms of Service

The Balentic website and Orca are, and are expected to continue to be, under development. Consequently, some of the features described in this Overview and/or on the website may not yet be available or may work differently. Some features may furthermore not be available to all users.